As any vintage Ferraristi knows, the Italian aesthetic sometimes places form over function. Pinninfarina is perhaps the most lovely coachworks still in existence. However the Prancing Stallions tended to be quite high strung and requiring significant maintenance to keep them gorgeous and running well. On the other hand, if one prefers function over form, Porsche won hands down: the internals were unquestionably reliable, providing repeat brutal-yet-refined high performance under grueling conditions. Literally the opposite of finicky.

In a silly sort of way, I like to think of the top half of Sandavore as the Ferrari part and the bottom half as the Porsche part. However, being wooden, bronze, and a multitude of varied fasteners, wooden hulls are nowhere near carefree. Shipright Andy Stewart at Emerald Marine Carpentry had already seen Sandavore in the straps early last summer and agreed that there were some things that needed further inspection. We coordinated a scheduled work period in October, which became November due to early winter storms.

As part of a long term, preventative strategy, Andy and I wanted to place Sandavore on a maintenance plan. This would require careful analysis and recording of the entire keel, every plank, every frame, and every fastener. Oh- and the rudder/prop assembly. Last year Andy saw what he believed to be a suspicious plank on the starboard side, which progressed from above-to-slightly-below the waterline. He suggested removal to determine why it was bulging slightly. I agreed, and progress began.

Old fishing boats tended to be assembled with planks “butting” on frames. Why? Because it was cheap and fast. As I was schooled by Andy, this is problematic: planks tend to swell over time and fasteners corrode. As thousands of ocean swells hit the sides over the years- especially the planks just aft of the bow- the pressure at the butts can cause a plank to pop open. Open butt below the waterline = boat sinks. The alternative is to butt planks on a dedicated block of wood somewhere between frames, which allows a greater surface area for the plank ends to be fastened, and in some cases bolts can be used (versus wood screws).

Although nothing critical was discovered during the dismantling, it provided the opportunity to observe the underlying frames and their condition. With a specialized boroscope Andy was able to look inside the planks at places that no human eye could see. Again, nothing of note: no split frames. Andy was particularly interested in the condition and types of fasteners. When he showed me the galvanized nails used when the boat was made, all I saw was horribly rusted stumps. “Oh these have some life left in them”, quipped Andy. However he was more concerned with the discovery of stainless steel Robertson drive screws alongside the galvanized. Diverging slightly into electrolytic chemistry, the marine environment (and especially the salt marine environment) causes dissimilar metals to corrode. Although the new screws were not in contact with the existing galvanized, just the proximity of stainless (highly corrosion resistant) to galvanized will cause the galvanized fasteners to corrode more quickly. In addition, stainless steel does poorly in anaerobic (oxygen free) environments. “It tends to thin out over time”, explained Andy. The decision was made to begin removing every stainless fastener from every butt, to be replaced with oversized galvanized screws and wooden plugs. This turned out to be the most time consuming job of the haul out period.

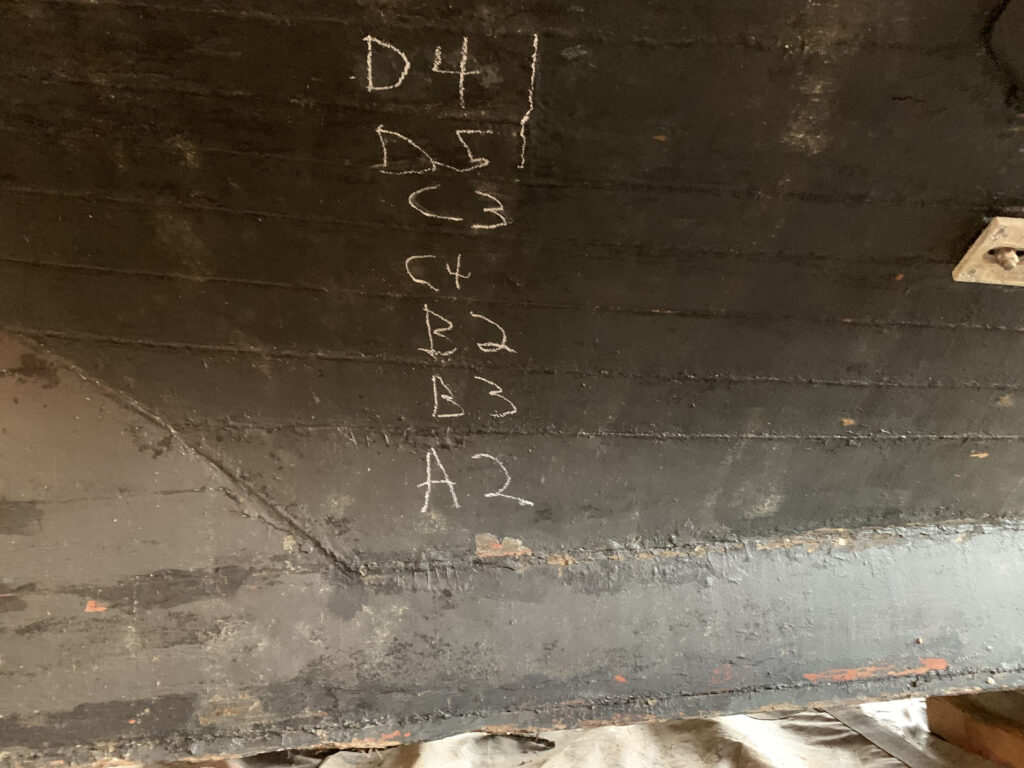

Next, it was time to designate every plank with an alphanumeric identifier. We did this partly to keep track of the butt joints repaired and partly to keep a record of any discoveries that would need attention at the next maintenance period. The first reason became less important as the decision to replace fasteners at each butt joint occurred.

There was evidence that the keel bolts might be rusting through, so the decision was made to install galvanized plates on either side in a “sandwich” fashion. Nicholas fashioned the plates out of 3/8″ from Skagit River Steel, and my awesome wife took them down to Seattle Galvanizing, I was able to bring them back for him to fit.

A thorough cleaning of the prop was warranted, to determine overall condition. The prop dome zinc was completely missing on this haul out, and there was evidence of “pinking” (leaching of zinc from the bronze). With a wrench it is possible to gently tap areas of each blade to determine if the pinking has started to cause the metal to become brittle; a dull thud is evidence of this. Nothing like that heard, thankfully!

Back to the plank:

Although it was raining almost the whole time, I was able to refinish the mild steel stem and get two more coats of Awlgrip on the gum wood panels. The steel was quite rusted and I’m now a complete convert to a product called Ospho. Three coats of Pettit Rustlok, then two coats of paint. Stunning!

14 days out of the water, bottom painting and at least a 1/2 dz other smallish projects later, Sandavore was slipped back in at the Anacortes City dock where I was able to take her back to her covered slip in La Conner. Overcast, still, perfect conditions- and it only began to rain 10 min after we tied up! Big thanks to Andy and his team at Emerald: Nicholas, Shawn, and Chief Frank. We’re in good hands.